This is a post about two little girls—one fictional, one real. It is also about one of the most fascinating mysteries in American literature.

This is a post about two little girls—one fictional, one real. It is also about one of the most fascinating mysteries in American literature.

Once upon a time, in the early 1920s, an eight-year-old girl in New Hampshire sat down at her parents’ typewriter. She began to peck out the tale of another little girl whose fondest dream was escaping from her parents and living in the natural world.

Some time later, she finished the tale. It was the length of a short novel. She had been writing stories since she was four or five, but this one was of rather greater magnitude, in size and quality. Dad and Mom knew it was something special.

Of course, many parents assume their little offspring precocious and very much above average. And it’s tempting to suppose that the girl’s father and mother were indulging in the same sort of wishful thinking. But these particular parents happened to be literary folk. Dad was an English teacher and writer, and Mom was also a writer. They knew books, and they knew the little novel was quite an achievement for a child their daughter’s age.

Now this was the era of manuscripts often existing as only one copy. No duplicates, no digital backups in the cloud. There was a fire in the family’s house. The only copy of the girl’s book went up in smoke.

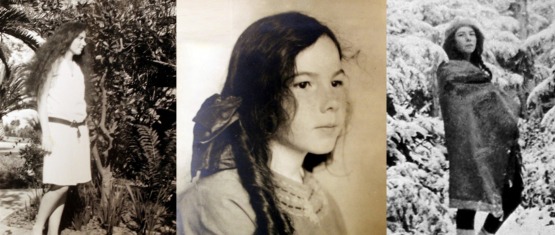

But this girl, whose name was Barbara Newhall Follett, was nothing if not determined. By the time she was twelve, she had managed to recreate her lost manuscript—or at least come as close as possible to what she had originally written.

Having surmounted this lofty challenge, she attacked another: she submitted her slim little novel of escape and freedom to Alfred A. Knopf, one of America’s most distinguished publishing houses then and now. That is rather like a twelve-year-old playground ballplayer trying out for spot on the Yankees roster.

Amazingly, Barbara succeeded. Knopf accepted her book. It was published in 1927 to great acclaim. For example, both the New York Times and the Saturday Review of Literature raved about it. Shortly after, she wrote a second novel, based on her real-life sea voyage on a sailing schooner. It was accepted for publication in 1928.

Then things began to fall apart for the young prodigy. Her father left Barbara and her mother, taking up with another woman. Barbara’s efforts to do travel writing with her mother came to nothing. The Great Depression hit. She was left with family friends in Los Angeles for a time and ran away. The case made national headlines.

Ultimately, she was forced to go to work in a secretarial bureau, where she did shorthand and typing. She wrote two more books, which went unpublished. But by the mid-1930s Barbara met a young man and married him. Things went well for a while, but sometime in 1939 she realized that her husband was involved with another woman. Toward the end, she hoped that he would take her back; that they could work things out. But it wasn’t to be.

In early December of that year, Barbara Newhall Follett Rogers, a genuine prodigy of American literature, walked out of her Brookline, Massachusetts apartment with $30 and a notebook. She was never heard from or seen again.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Barbara’s debut work is called The House Without Windows & Eepersip’s Life There. And in its very eccentric way, it is an amazing tale masterfully written.

Barbara’s debut work is called The House Without Windows & Eepersip’s Life There. And in its very eccentric way, it is an amazing tale masterfully written.

Eepersip is a little girl of about the author’s age who wants above all else to escape the limitations and obligations of living in a house with the weights and responsibilities of family. She wants to enjoy a sensual life purely in nature. So she makes her escape and goes to live in a nearby meadow, where she befriends the deer and the butterflies, and develops a fond relationship with Chippy the chipmunk and Snowflake the kitty. She weaves herself a dress of ferns, goes barefoot, and eats roots and berries.

Her parents, of course, have noted their daughter’s absence and come hunting for her. But the grownups in this story prove singularly inept at recapturing the errant child. She escapes their clutches again and again. One of the most interesting things about Eepersip is that she shows no particular sentiment or affection for her mom and dad; she basically wants nothing to do with them, though it seems they’ve treated her with warmth and fondness. The only love she is interested in is the love of the natural world.

(Nowhere in the novel does Eepersip deal with the Darwinian nature of the natural world. For the most part, predation and disease and death play no part in this fable. It is almost all butterflies and flowers and frolicking—lots and lots of frolicking. However well young Barbara may have written, she was still a child with an idealistic, gauzy view of the world.)

Here, Eepersip teaches herself how to live her new life:

For hours every day she practised running, leaping, dancing, and prowling, until she was as fleet as a deer and as soft on her feet as a lynx. She had practised leaping over high objects, and if someone were chasing her, she could now escape being cornered by jumping a fence. She had trained herself until, even without a running start, she could clear the back of a standing fawn; or, with a start, a large buck standing full height. All these exercises made her light as a feather and graceful as a fern.

By and by, Eepersip leaves the meadow, and any chance that her parents have of reclaiming her passes. She proceeds to the seashore and the ocean, leaving Chippy and Snowflake for good. And then it’s on to the mountain peaks. Yes, she’s still barefoot and in her fern dress, and has no trouble at all with frostbite or starvation.

She encounters only two people along the way with whom she chooses to spend time. A random boy who becomes her temporary friend. And her own little sister, whom she spirits away from her mom and dad. But little sister, to Eepersip’s huge disappointment, ends up missing the parents. To her credit, Eepersip takes her back home.

The House Without Windows isn’t only about finding an escape from the dreary world of adults, as embodied by parents. It is about finding bliss in an incredibly idealized natural world. In fact, the book—as it unfolds in Eepersip’s point of view—comprises forty-five thousand words of sheer, extended ecstasy. It is, in its naïve way, a depiction of pure hedonism. The girl is over the moon to be in nature for every minute of every day.

In one place, among dark ferns, grew columbine, gay little gypsies curtseying in the breeze. Their colours spoke to [Eepersip] of dawn, gold sunset and white clouds, snow-banks fringed with icicles, night sky entwined with moon beams, black clouds and radiant sun, or orange, yellow, and scarlet leaves—autumn leaves. She gathered some; and made a rainbow wreath of blossoms; and curling about her hair, they danced again…

And…

That day Eepersip was even happier than usual. She floated about, visiting each flower, each bush and tree. She played games with the butterflies, the games she had played on the old meadow that first summer of her life in the House without Windows. When she rested, she sat on top of a laurel-bush, and not a twig bent beneath her. The slightest breeze blew her about, changed the direction of her dance. Butterfly after butterfly flew to her, flock after flock, as if they had some message to tell her; and after each visit she was happier than before. Yes, they were messengers, these happy creatures; messengers who came to whisper her a secret—a secret from Nature, a secret of the beautiful meadow…

And, finally, she becomes what nature has been preparing her for.

She was a fairy—a wood-nymph. She would be invisible for ever to all mortals, save those few who have minds to believe, eyes to see. To these she is ever present, the spirit of Nature—a sprite of the meadow, a naiad of lakes, a nymph of the woods.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

But, of course, the real world was not so kind to Barbara as the house without windows was to Eepersip. It’s hard to imagine what it must be like to achieve such a height at such a young age, then to have everything come crashing down. But that, of course, is the real Darwinian world of art—the author or composer or artist is no more entitled to continued success than the chipmunk or the butterfly or the deer.

And the mystery of Barbara Follett?

Did she live to write another day under some other byline? Did she become a wife and mother in a family that had no idea of her secret? Did she hole up somewhere and work the rest of her life as a secretary or English teacher? Or did she end up a Jane Doe in some distant morgue?

We’ll never know. But her story deserves re-telling. As a biography. As a movie. The House Without Windows deserves a place as a classic of American children’s literature.

If you want to read the book—and I think you should—you can download an e-book or PDF version by clicking down below. There are also links to the website maintained by Barbara’s nephew and to the article in Lapham’s Quarterly that brought Barbara’s incredible story to my attention.

And now, if you don’t mind, I think I’d like to go outside and dance with the crocuses that are beginning to poke up out of the ground.

You can download an e-book copy of The House Without Windows right here.

This is Farksolia, the website devoted to Barbara Follett.

And here is the Lapham’s Quarterly article that aroused my interest in Barbara.

April 12, 2015 at 3:27 pm

Thanks for introducing this incredible story! It sounds fascinating and I can hardly wait to read it.